in memoriam

Carolyn Autry

David Beronä

Yvonne Browne

Margaret-Ann Clemente, 2021

Barbara de Groot

Rolf Eiselin

June Felter, 2019

Barbara Gunther, 2021

Karl Kasten, 2010

Anthony Lazorko

Ann Lindbeck

Peter McCormick, 2011

Kathryn Metz

Barbara Milman, 2019

Nathan Oliveira, 2010

Roy Ragle

Eleanor Rappe, 2021

Claudia Steel, 2016

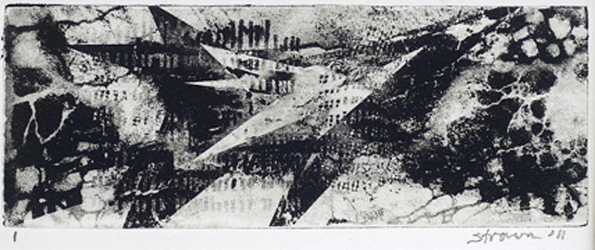

Mel Strawn, 2020

Carol Summers

Margaret Warner Swan

Jennifer Tancreto, 2015

Patricia Tavenner

Beth Van Hoesen, 2010

Lila Wahrhaftig, 2020

Mary Warshaw

Jean Eger Womack

Mark Zaffron, 2013

Margaret-Ann Clemente, 1949–2021

Margaret-Ann was born in Paris, France, to Jasper Clemente and Genevieve Clemente, née Figeac in 1949. She received a B.S. in filmmaking and graphic design from American University. She also attended Pratt Institute and received diplomas from École St. Roch and École du Musée du Louvre. She was proud of both her Sicilian and French heritage, had an insatiable curiosity and zest for life that was infectious to all who knew her, and loved to learn.

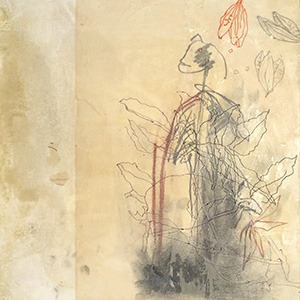

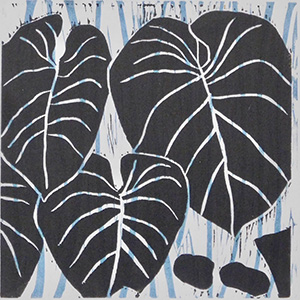

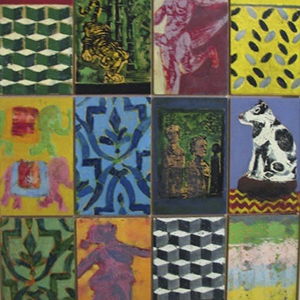

Margaret-Ann had a passion for art and pursued a career as a fine artist across a variety of media including serigraphs, monotypes, acrylic painting, and drawing. She loved planet Earth and its biotic community. Much of her art focused on endangered animals. She was a member of the California Society of Printmakers, a board member from 1999–2005 where she served as the editor of the News Brief among other roles. She was also a member of the Pacific Art League, Pacifica Art Guild, and Coastal Arts League in Half Moon Bay and an artist-in-residence at Kala Art Institute. Her work has been exhibited at numerous galleries in Half Moon Bay and throughout the Bay Area as well as other national venues. Her work can be found in private and corporate collections in the United States and Europe including a piece in the permanent collection of the Museo Italo Americano in San Francisco.

Barbara Gunther, 1930–2021.

Barbara was born and grew up in Brooklyn, New York, living with her parents and brothers over the family’s candy store. Among her talents was the mixing of excellent egg creams.

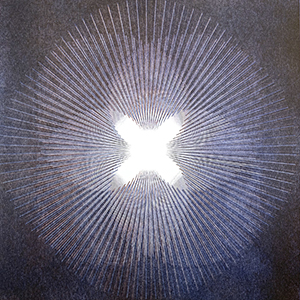

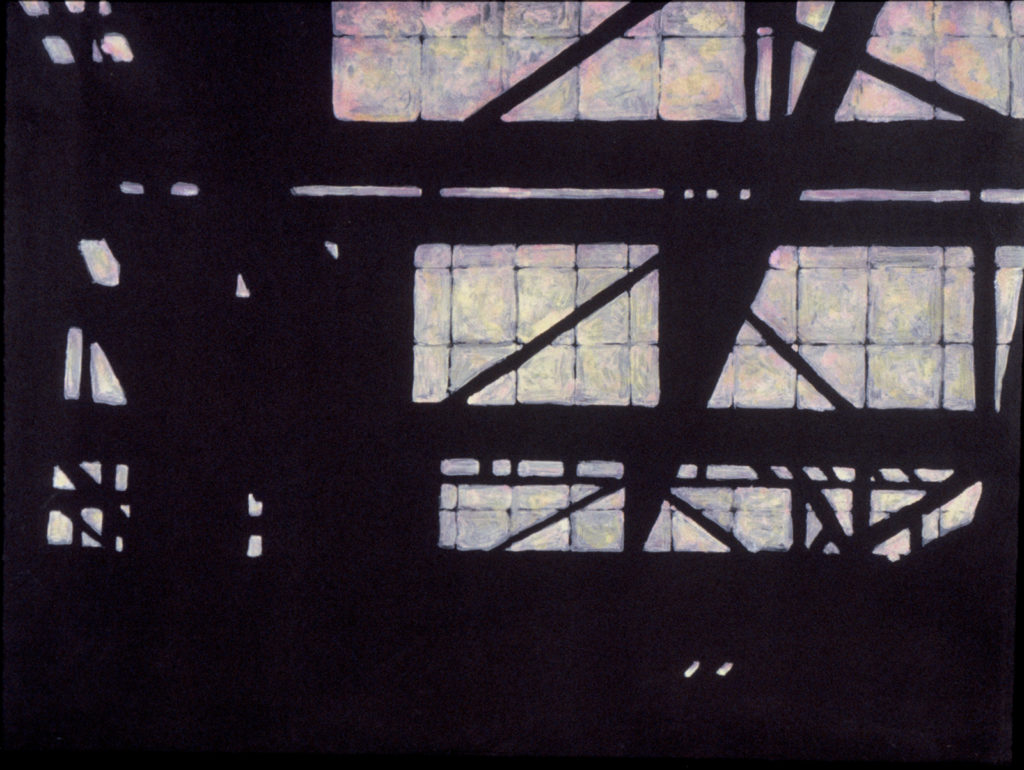

When Barbara was in junior high school, a teacher noticed her drawing ability, and took her to visit the art museums of Manhattan. That experience helped inspire a 55-year career as a painter and lithographer; her work is collected in the Museum of the City of New York, among other places, and can be viewed at www.barbaragunther.net. The play of light, darkness and shadow, which fascinated her as a child watching the broken light stream through elevated subway tracks near her home, was an enduring theme in her art — and a source of inspiration during wide-ranging travels she undertook as an adult.

After attending New York City’s High School of Music and Art, Barbara graduated from Brooklyn College at age 18, majoring in history. That same year she married Gerald Gunther, who became a professor of constitutional law at Columbia and Stanford law schools. They were married 53 years, until his death in 2002.

After returning to school in her forties and earning a Master of Fine Arts degree from San José State University, Barbara taught life drawing, color theory, and other visual arts courses at Cabrillo College, in Aptos, California, for 20 years. Beginning in 1965 she was a professional artist, and was working on a large canvas during her final year. She was a member of vibrant art communities in San Jose—where her first studios were at the Citadel—and downtown Palo Alto, where her last studio was in the former Cubberley High School, and the Santa Cruz area. During her career Barbara had 15 individual exhibitions, and a greater number of group exhibitions, at galleries and museums in the United States and Europe.

Eleanor Rappe-Rauguste

Former CSP President Eleanor Rappe died peacefully at home on April 5, 2021. Eleanor lived in San Francisco, California for 30 years, where she had established a career as a prominent printmaker, exhibiting several shows at major museums, including the De Young Museum, and the San Jose Museum. Eleanor retired as the chair of the art department at City College of San Francisco in 1994, having previously taught a large cohort of printmaking students, The Fort Mason Print Makers, who regularly exhibited their work and became successful artists in their own right. Some of her prominent students included the renowned San Francisco based Hungarian born artist, Theodora Varnay Jones, her dear friend Chris Knipp and the American artist Anita Toney.

Eleanor started her California career at the Vorpal gallery of San Francisco, with a one woman painting show. After obtaining her MFA in printmaking at SFSU where she studied with James Torlakson among others, Eleanor began to explore a number of printmaking techniques, including chine cole, collograph, etching, monotypes, and three dimensional forms. She later turned to digital arts. Eleanor’s work evoked the ruins of Greco-Roman antiquity, including etchings that imitated the stone forms of pavements, fragments, and larger structures from photos she personally took during her extensive travels throughout the Mediterranean, Middle East, and North Africa.

Lila Wahrhaftig

Lila joined CSP in 1984. She was active on the CSP board from 1986 to 2010. Two years after being admitted to CSP, Lila joined the CSP Board of Directors as Publicity manager, serving in that role for a year in 1986. In 1987 she assumed the role of liaison and promoter of CSP’s Patron Membership. Lila then began chairing the Brown Bag Committee, which arranged visits to CSP member studios. Lila continued organizing and chairing the CSP Brown Bag studio visits for five years, from 1992 to 1997.

Mel Strawn, 1929—2020, Salida, Colorado. Strawn’s contributions to the field of fine arts include co-founding the Bay Area Printmakers Society in 1955 and pioneering artistic use of computer technology in 1981 with basic code before the advent of software packages and digital cameras. Strawn earned a master’s degree in fine arts from California College of Arts and Crafts in 1956. He went on to teach art at Midwestern University and Michigan State University. He directed the schools of art at Antioch College, the University of Denver and Western Michigan University. After retirement he continued to teach at Colorado Mountain College. Strawn lived in Salida for the past 30 years as an active artist, leader in the Salida arts community and climate activist.

To balance his solitary work as a painter and printmaker, he enjoyed participating in community discussion groups. He shared his knowledge and collection of writings on art history and global trends of multiple disciplines with the informal Art Book Club. In the Bridging the Divide group, which explored effective communication skills for crossing social divides, he prompted members to look below the surface and search for reliable evidence. Strawn was passionate about fighting climate change. He was a founding force behind 350 Central Colorado and prompted discussion of the planet wherever he participated. A retrospective of his work, All Together Now, 1940s-2000s, was exhibited at the Denver Public Library in 2007. The library also holds archives of his papers.

The Salida Council for the Arts inaugurated an achievement award in his name and awarded him the first annual honor. Strawn contributed his thoughts and images in his blog, Brushed in articles and in self-published books.

A 2009 article on Strawn by Mike Rosso was published in Colorado Central Magazine.

Mel’s Theoretical Observations on Solarplate Printmaking

June Felter, 1919-2019. Artist, printmaker, painter, 99 years old and still making art.

June had been an active member of California Society of Etchers, exhibiting in the 1960s with Kathan Brown (of Crown Point Press), John Ihle, Beth Van Hoesen, Helen Breger, and Karl Kasten, all stalwarts of the Bay Area art/print scene.

She served on the Executive Council that wrangled the details of the merger of two print societies into one: Bay Printmakers (est. 1955) and California Society of Etchers (est. 1912, announced 1913) into The California Society of Printmakers.

Her parents died when she was very young, and she grew up in the Tom and Grace Scanlon family. She became a fashion illustrator, who later created war bond ads. Before the war, June discovered skiing in the Sierras, where she met future husband Richard Felter. They were together until his death in 2000. In the 1950s, inspired by California Figurative painters approaching reality with the freedom of abstraction, June studied with Richard Diebenkorn, and became a colleague of Elmer Bischoff and Wayne Thiebaud. In her landscapes, nudes and complex still-lifes, June’s work was admired for its graceful spontaneity. She taught art to children and figure drawing to adults at SFMOMA. Her etchings are featured in the book Why Draw a Live Model? by Kathan Brown.

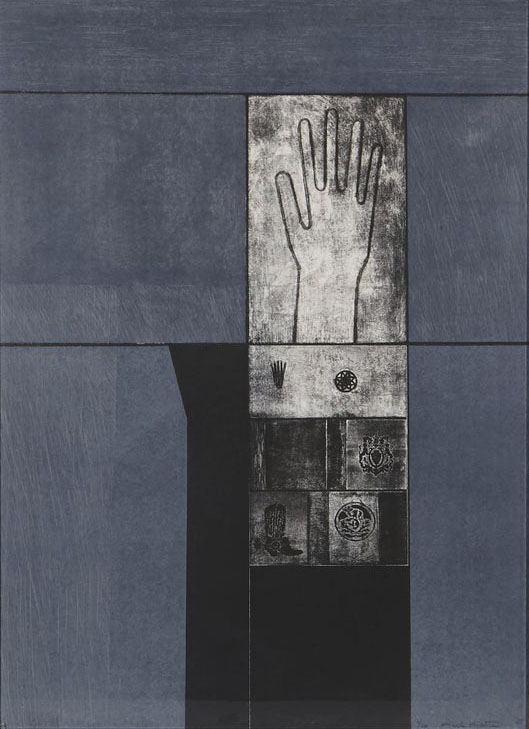

Barbara Milman, 1941-2019, joined CSP in 1995. She was a strong presence, a person that many admired. She was on the board in various positions between 2004 and 2010 including President for two years.

It was just a year before her death that she published The Memory Palace, her illustrated novella “interweaving fantasy, the natural world,” in the words of a reviewer, “and the reflections of a narrator who is facing death—her own and that of the planet—with courage, humor and outrage.” The book capped Milman’s double career, the first as a lawyer, beginning with civil rights work in the Mississippi of the 1960s; private practice with her first husband, Jonathan Shapiro, and others in Boston; as counsel to a Massachusetts Commission investigating corruption in the state’s public housing program, and ending as chief counsel to the California Fair Political Practices Commission and its Assembly Rules Committee in 1993. In 1994, she made a complete switch, quitting the bar to devote full time to the art that she said was always her great love, particularly printmaking and handmade artist’s books, much of it created in her studio in El Cerrito, CA. Later she told an interviewer that her legal career was “a 25-year detour.”

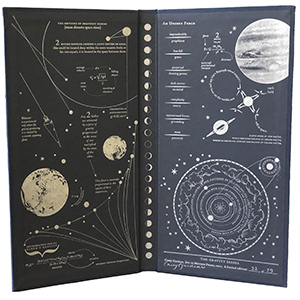

Over time, she produced more than 36 artist books in small editions. They are notable for their mix of printmaking, collage, and digital techniques, often in counterpoint with short but powerful texts and striking page designs. They’re now in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, the National Museum of Women in the Arts and Yad Vashem in Jerusalem and figure in the Special Collections of over 35 university libraries. Perhaps her most important work was the artist’s book “Light in the Shadows”, later issued as an illustrated volume with the same name by Jonathan David Publishers.

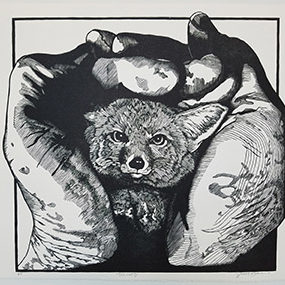

Milman had scores of solo exhibitions, was artist in residence at institutions both in this country and in Europe, taught printmaking and won numerous awards. “My printmaking,” she wrote, “is based on traditional relief, especially linocuts, which I mix with other printmaking techniques, including digitally based methods. My artist’s books combine hand printmaking with digital and photographic elements. I transfer images between the prints and the artist books. The works in the two media complement and reinforce each other.” But the art, like much of the legal work, was always infused with social passion, the Holocaust, prisoners’ rights, and particularly, in recent years, the environment and the extinction of species. The ironic theme of “The Memory Palace” is a museum devoted to extinct birds and the stories they tell about their own extinction. Not coincidentally, perhaps, her second husband, Daniel Rancour-Laferriere, a writer and Russian scholar, whom she married in 1979, is a birder.

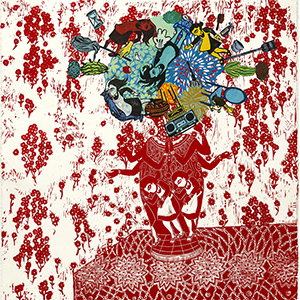

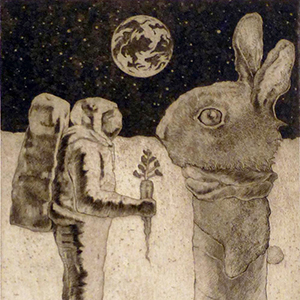

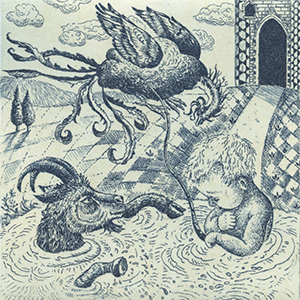

Image: Shtetl, linocut & woodcut, 24″ x 22″

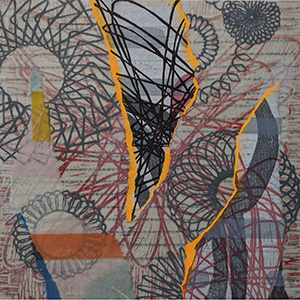

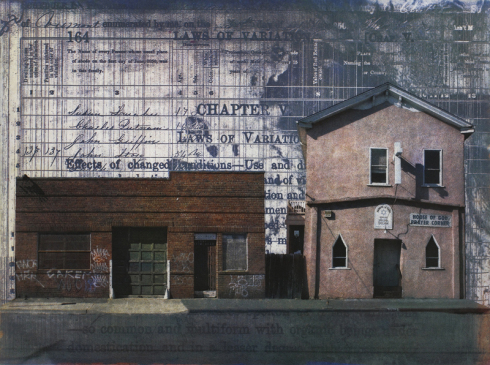

Mark Zaffron, 2013. Founder and Director of the Center for Research, Art, Technology & Education (The CRATE), a non-profit printmaking studio in Oakland, California. Zaffron taught Printmaking at the San Francisco Art Institute and the Academy of Art University. He had been a visiting artist at numerous institutions including Cooper Union, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Northwestern University, The Corcoran, The Museo Nacional in Buenos Aires, and the Galilee Intaglio Studio in Israel. His work has been prominently featured at venues such as the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Seattle Art Museum Gallery, Plains Art Museum, Barret House Galleries in New York, Triton Art Museum, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Artist’s Gallery.

“I find that making art is about satisfying a series of curiosities–visual, technical, and intellectual. I enjoy the challenge of giving visual and physical form to what was once an abstract notion. Thematically, my work is concerned with a long-held fascination with evolution as it applies to human environments. With the neighborhoods surrounding my studio as subject, the work examines adaptation, mutation, and the influence of a specific environment on the people and infrastructure. The images are composed of many layers of information that offer a great deal of visual complexity with which to experiment. Similarly, I explore numerous ideas borrowed from diverse fields of inquiry–particle physics, abstract mathematics, economics, anthropology, etc. These generate contextual layers to create a conceptual complexity that is central to the work.”

Beth Van Hoesen, 1916-2010, is first mentioned in the CSP archives in 1958 when she helped organize a few exhibits, and in 1959 she was President of the Society. She was awarded Honorary Lifetime Membership to the CSP in 1996. A few of her etchings that were published by Crown Point Press in 1965 can be viewed on the Annex Galleries website. Some nice illustrations of her animal paintings and prints are seen on her Facebook page, as well as on the Nancy Dodds Gallery website.

Nathan Oliveira, 1928-2010, born in Oakland, California, exhibited with Bay Printmakers Society beginning in 1956. In 1968 Bay Printmakers and California Society of Etchers merged to become California Society of Printmakers. Oliveira was awarded Honorary Lifetime Membership in CSP in 1993.

Peter Leone McCormick, 1943-2011. Peter lived in San Francisco most of her life working as a bookkeeper, but her true love was art. She was an accomplished fiber artist, weaver, and printmaker. There was nothing Peter liked better than a day at the beach or a good hike – nature was her focus and inspiration. Her artist’s statement expresses her appreciation of the process and the value of collaboration with fellow artists.

In her early years Peter worked on Broadway in San Francisco and was a friend of many of the most noted performing artists and colorful North Beach beat generation characters of the 1960’s. She worked at the Hungry I and managed The Boardinghouse for several years. Later she was a partner in a successful San Francisco design firm.

A kind, loyal, and generous friend, Peter was an avid reader and art historian. Conversations with her were wide-ranging, educational, always interesting, always punctuated with wit and humor, and often with colorful stories of her experiences. She will be missed by her many friends – she was an exceptional person.

Peter was a member of California Society of Printmakers, Nature Printmakers Society, San Francisco Women Artists Association, Mid-Atlantic Print Council, Graphic Arts Workshop, and the Southern Graphics Council. Her award-winning works have been shown at many exhibitions and are held by the diRosa Art & Nature Preserve, Napa, CA and many private collections.

Karl Kasten 1916 – 2010

Kasten taught printmaking at UC Berkeley from 1950 until 1983 when he retired as professor emeritus of art. In 1988 Kasten became an honorary lifetime member of California Society of Printmakers. Four years later, in 1992, Kasten donated an 1890 Kelton D-wheel copperplate press to the Bancroft Library where it resides in its press room, and is still used to teach history of the book and letterpress. Over the years Karl has lobbied Bancroft curators Bill Roberts and Tony Bliss to exhibit printmaking materials, selections from the CSP archives, and works of CSP members.

Karl Kasten: A Rembrance by Kevin Radley

If you drive or look east you begin to see the blue abstraction of the Sierra Foot Hills. There is a theory in art that the further away an object is the more abstract it is and because of the distance the color of the object turns blue for the light is cooler. The closer one gets the more vivid the shapes become, and the clarity of color comes clearer warmer, more vivid. This is what my relationship with Karl Kasten was for the last ten years. First from a distance and in time the colors became richer and warmer and the details became clearer. I saw how remarkable an artist, a teacher and a man he was.

Nearly every day at 11:30 Karl came into the Art Department office to check his mail, chat with folks and make some phone calls and say Hi. It was easy to talk with him. It didn’t take him long to find out that I ran the noon lecture series for the department. It didn’t take long for him to drop the question, “So Kevin, how about I do a lecture one of these days. The students would love it.” Karl wasn’t shy to ask for anything, and he was nearly impossible to say no to. So I scheduled him for a noon talk and hoped for the best. That wasn’t something I needed to worry about, especially filling the room with attendees. Karl seemed to have his own audience of friends family, colleagues, folks he had over lunch, and perhaps a dealer or two. As for the talks themselves, they were less like lectures than intricate weavings of the ideas of the history of art, from Lascaux to Matisse, from Cezanne to post-modernism, from the ying /yang symbol to his theories of pictorial composition, from the beauty of egg tempera to the physical splash of abstract expressionism, from the early formation of the newly developed UC Berkeley Art Department in the 1920’s to The Berkeley School, and always mentioning his lifelong mentor Worth Ryder, and the remarkable array of artists that influenced Karl throughout his artistic life: Hans Hoffman, Wilem De Kooning, Chiura Obata, and John Haley among so many others.

As the cycle of life tells us, our history is what provides us with the reasoning for the moment we live in. I too love that department: it gave me the reason to be, to work, to teach to shape the future. There was a kinship I had developed with Karl through a couple of earlier lectures he presented. So in 2007 I popped the plan. I told him I wanted to show his work in the gallery as a retrospective and an homage to the early years of the Art Department and in the place that was named after his great mentor and the house he had helped build, The Worth Ryder Gallery. Karl loved the idea. I really didn’t know much about Karl’s work, but I was certain that the exhibition would be sensational, and we both relished the idea of bringing a historical perspective to the department.

The next step, lunch. That seemed to be Karl’s way of making concrete the plans for the show. First stop: the Faculty Club. We meet in the Great Hall. I had been in the club a number of times. For me it was more of an act of subversion, waiting to get thrown out. Karl on the other hand walked easily, smoothly among the distinguished emeriti, Nobel recipients and educators alike. He belonged there and he loved it and knew it. He takes me down a short hall to a sign that reads “the O’Neill Room,” and opens the door. There on the wall a fresco completed in 1930 by faculty member Roy Boynton. Karl restored it to its original beauty. He didn’t stop there. He saw the perfect opportunity to enshrine the small hall with Berkeley’s first art faculty members: Chuira Obata, Erle Loran, Margaret Petersen ,Worth Ryder and others. Suddenly it came to me this small room was more than a show or an exhibition but an endowed shrine paying homage to the university’s first gesture into modernity through its art faculty. Quite a revolution. He was there, I was stunned.

Next stop the “Chateau”, Karl’s house which he called the Chateau. Chateau? We all love our homes, kings’ castle and all, but here I am stopping at the front of the house. I’ll be damned, it is a chateau! That was the last time I remotely thought anything cynical about what Karl would say. He was never cynical or dismissive, and I was served a lesson.

Karl answers the door, Georgette standing behind. The house is filled head to toe wall to wall with art, objects, paintings by friends colleagues, his work, students works, copper objects from who knows where, Italian Renaissance painting, and his newest find, four Afghan Buddhist sculptures. It’s stunning. Georgette was charming, tall and cracking jokes at the drop of a hat. Two hours later we have traveled the world of stories, of the past, of Worth Ryder, Chiura, former students, art ideas, etc. The sandwiches are so good.

Karl had the same drink every lunch, Bulgarian Buttermilk and this brown liquid he poured in every once and a while. For some reason I thought it was prune juice, I tried the buttermilk, but not the prune juice. I ask him “why do you pour prune juice in the milk”, “Prune juice”, Karl laughed, “that’s not prune juice, silly, it’s coffee.” Prune Juice. It’s one of those moments where I was just a dumb young dog.

As for the exhibition, it was to be in three parts, “The Berkeley School “ in the small gallery, Karl’s work, and an array of students’ work in the back gallery. About the Berkeley School: a number of the first faculty had studied with Hans Hoffman, it was Hoffman’s ideas that pushed this newly founded Art Department into the Modernist trajectory. It was Worth Ryder who championed the call and it was Karl as a young student in Worth’s class that seemed to have absorbed all the precepts that Hoffman put forth. Ryder knew it, saw it, and I’m totally convinced that Karl, in Ryder’s eyes represented the next generation of artist/educators in which the young department needed to invest, even if he was as a student.

One of the first steps in curating an exhibition is to look for the earliest works that help shape an artist’s ideas. Meeting at the “Chateau” proved to be a treasure trove of Karl’s art, his colleagues, students, and so much more. One painting caught my eye nearly instantly. It seemed to firmly establish what Ryder and his colleagues saw in Karl’s work. That painting was “F Train”, an astonishing egg tempera.

Completed in 1938 while Karl was in his last semesters as an undergrad at Berkeley. “F Train” was composed by series of neatly constructed triangles that create the platform, beautifully proportioned rectangles create the stairs, and a hot red sliver controls the center of the work. Spread throughout the composition a series of orange and hot red Y shapes paired, grouped and gathered over the works surface. It is a remarkably Bauhausian/ Constructivist work with a dash of Duchamp and it’s egg tempera! Again, it’s egg tempera. Karl is 22 years old. I loved that piece. At Worth’s insistence, Karl would join the Berkeley faculty in 1949.

What Worth Ryder and his colleagues saw in this dashing young man was his audacity to fall into the realm of the modern. He seemed to be whisked away by every aspect of what made great ideas, the pleasure of leaping into the unknown and the skill to shape it’s outcome into something tangible and beautiful. Karl also had the ability to share that adventure and that audacity with other artists, like Hoffman, and De Kooning and, deepest and most importantly in his heart, his students whom he guided and encouraged for decades. Artists like Adelie Bishoff, Eileen Downey, Nancy Genn, Sonya Rappaport, Jean Lowe, Walter Askin, BB Smith. Bruce Beasley and Norman Kanter. Whose work we still are moved by and respect.

In the end I’ve some to realize how many of us now share that same audacity of art, adventure, of sharing our ideas and investing in the unknown.

Kevin Radley, Director of Worth Ryder Gallery 1993 – 2008

UCB Department of Art Practice.