Felicia Rice: Artist, Printmaker and Publisher

by Kent Manske

Foothill College, Los Altos Hills, California

Kent Manske creates images and symbols to inquire, process, manage, convey and assign meaning to ideas about human existence. He uses printmaking and book publishing processes to create one-of-a-kind and limited-edition works on paper. Manske was Art and Design faculty at Foothill College from 1990–2015. At Foothill he developed the printmaking program to include non-toxic processes, paper making and artist books. Manske has a BFA from the University of Wisconsin Eau Claire and an MFA from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His work can be found in public and private collections including the San Francisco Fine Arts Museums and the Oakland Museum of California.

Abstract

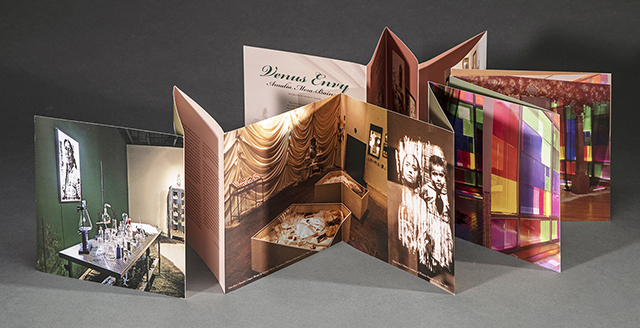

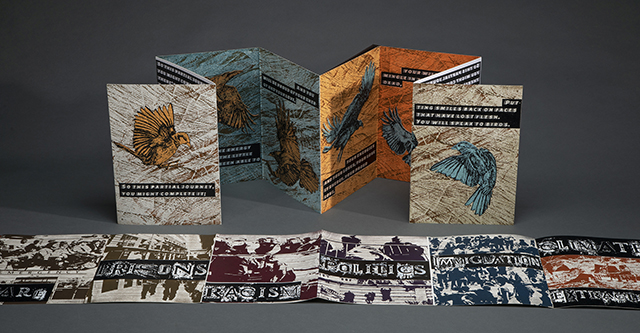

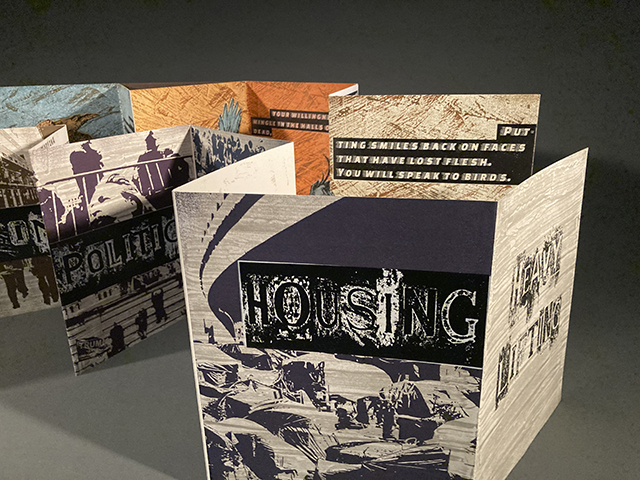

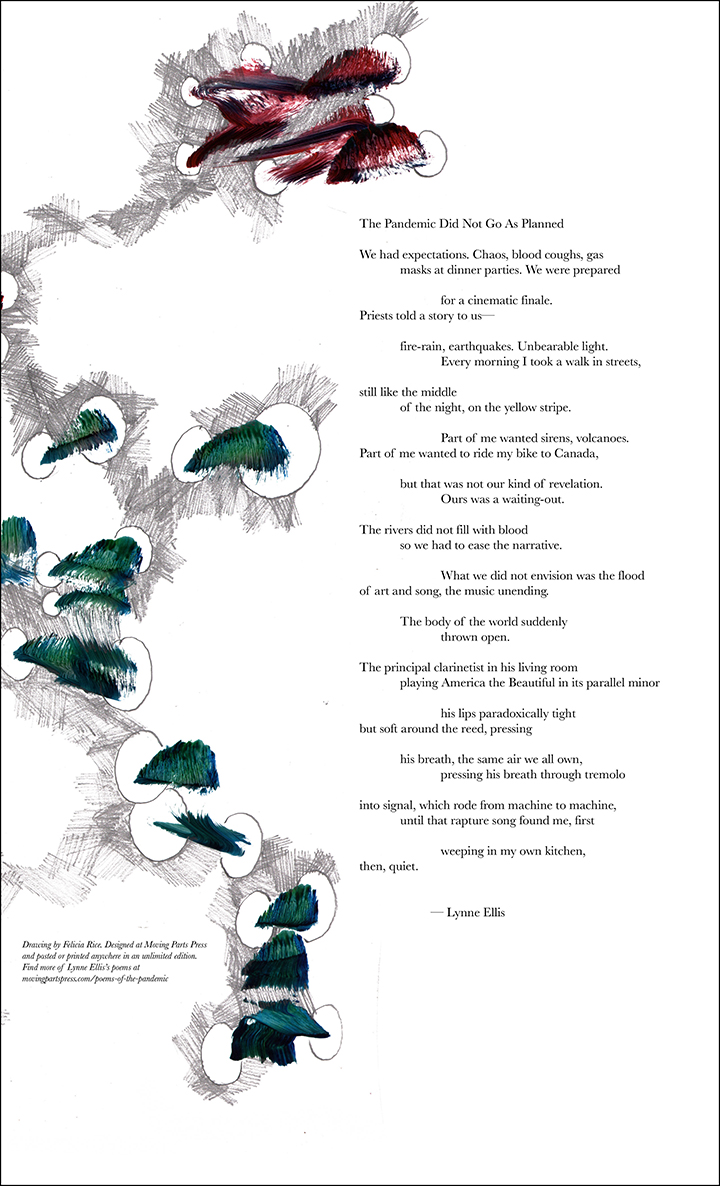

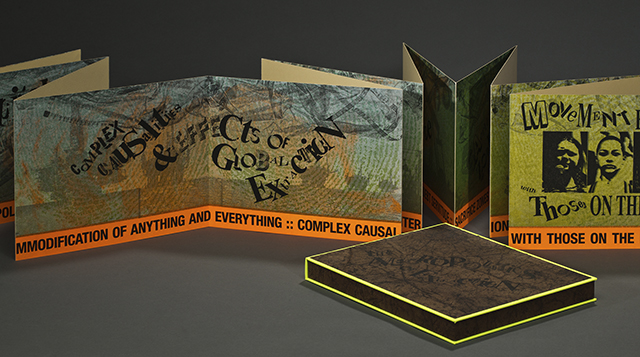

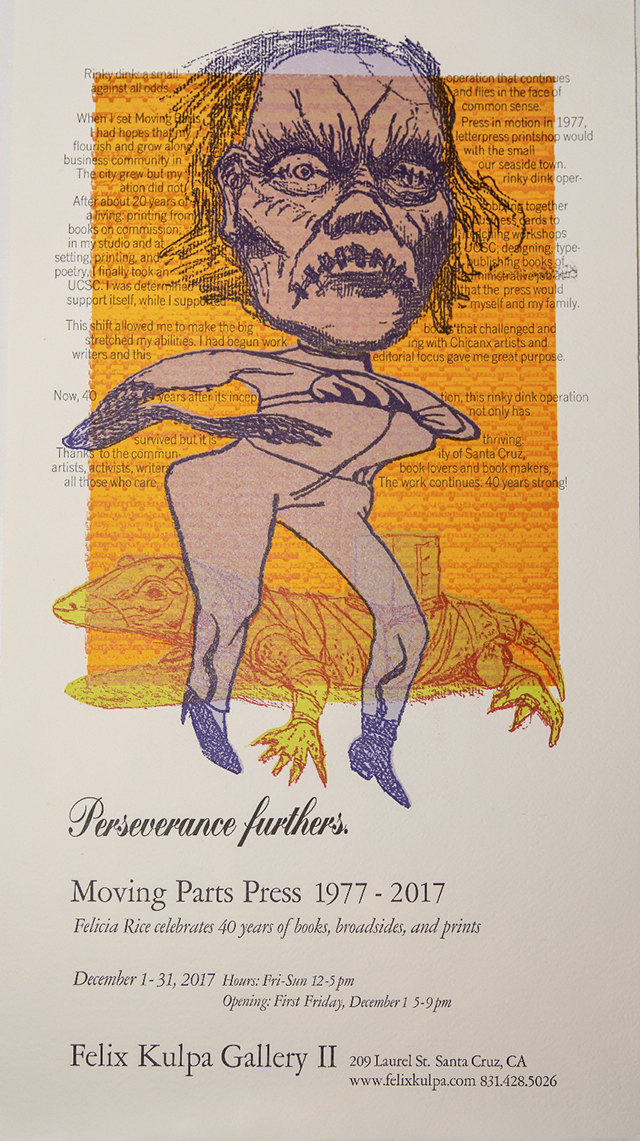

In 2017, noted Californian printmaker and publisher, Felicia Rice celebrated a 40 year career with a solo exhibition at Felix Kulpa Gallery in Santa Cruz, California. On exhibition were books and prints which were the products of Rice’s history of collaboration with California writers, poets and artists. In August of 2020 Rice lost her print studio and inventory of artists books to a devastating megafire in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Eight hundred individuals, institutions, and organizations donated to the rebuilding of Moving Parts Press at her family home in Mendocino. New work in response to this crisis was the subject on her article, Heavy Lifting, in CSP’s 2022 journal, Metamorphosis: Printing Under Pressure.

The following essay is an edited version of a conversation conducted during Rice’s 2017 showing at Felix Kulpa Gallery. It reveals RIce’s history as a printmaker and publisher from her early days growing up in Mendocino, California to the time of her celebratory exhibition in Santa Cruz.

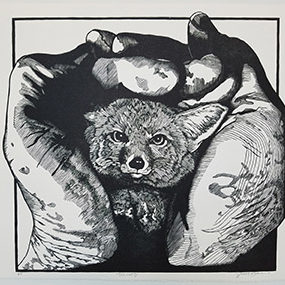

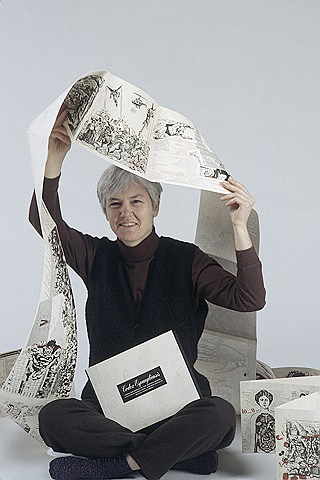

Felicia Rice with her books at Felix Kulpa Gallery in 2017

Introduction

Felicia Rice, well known for her fine press work and collaborative books, celebrated 40 years of Moving Parts Press in 2017 with a solo show at Felix Kulpa Gallery in Santa Cruz, California. Two years later the Moving Parts Press studios, along with Rice’s home, went up in flames in the now historic CZU Lightning Complex Fires in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Rice has since relocated to Mendocino, California, and Moving Parts Press is back in action.

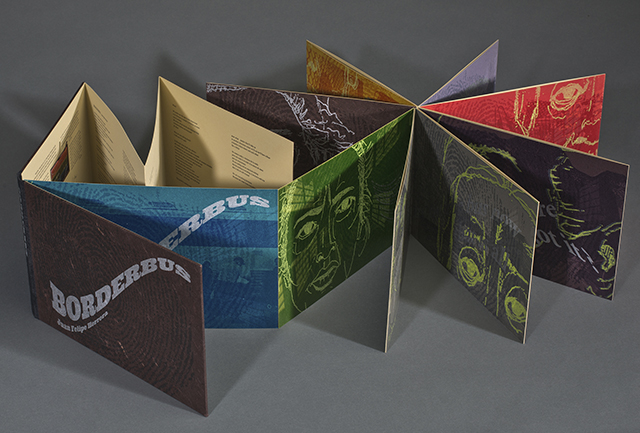

Rice has worked with notable Californian artists and writers including: Amalia Mesa-Bains, Francisco Alarcõn, Beau Beausoleil, Elba Rosaria Sánchez, Juan Felipe Herrera, Enrique Chagoya and Guillermo Gómez-Peña. As Moving Parts Press, Rice has received the Rydell Visual Arts Fellowship, Elliston Book Award, Stiftung Buchkunst Schänste Bücher aus aller Welt Ehrendiplom, and grants from the NEA, CAC and the French Ministry of Culture. Rice celebrated her history as printer, publisher, artist and collaborator with Perseverance furthers: Moving Parts Press 1977–2017.

I visited Rice during her exhibition at Felix Kulpa Gallery to experience the work, talk about making books and working with other creatives. This is an edited version of our conversation.

Our Conversation at the 40 Year Mark

Kent: You started Moving Parts Press in 1977 as a printshop in downtown Santa Cruz. How did you come to letterpress?

Felicia: When I was a kid a friend’s mother had a letterpress in the family room. It was a little table top pilot press. I can remember standing in the room and seeing it, and maybe touching it.

My folks were artists and teachers: my mother was a sculptor and kid’s art teacher. I grew up in her art classes and was exposed to all types of fine arts. My parents were founding members of the Mendocino Art Center. My father was a mosaic artist in the Art and Architecture movement in San Francisco working with Lawrence Halprin. He did pool bottoms and walls. Later he made independent fine art animated films.

The critical point came after I had left home. I was living in Berkeley around the corner from David Lance Goines’ studio and letterpress shop. My mom accidentally sent me one of those San Francisco Chronicle Weekend Edition articles on “Letterpress Printers of the Bay Area.” Adrian Wilson, Jack Stauffacher—there were about five of them. She accidentally sent it to me instead of my older sister. So I’m reading this thing and looking in the window at what’s going on around the corner. I started thinking this might be something I could get into. It didn’t necessarily mean I had to stay with it. I was 18 or 19 and thought maybe I could learn more. I went to Laney College which had a print and graphics program. The instructor said, “If you want to be a printer you need to get into computers.”

It was a time when there was a lot of support for crafts. A lot of my peers who grew up in California were carpenters or in the trades, which were highly respected. And the newspapers listed a lot of jobs for printers; so I thought I could be a printer. I could get work. At Laney there was some old letterpress stuff, but there was mostly this idea that one would go on to computers. It was interesting. I had also taken a printmaking class in Oregon around this time. I thought I could go to school for this but if it was just a fluke I could change my mind and do something else. I started looking around for print programs. There wasn’t really anything going on in the Bay Area. I came down to Santa Cruz with a friend to visit the school, and a friend of my friend said there was a press in the basement of Cowell College dining hall. So we went down there and there was this beautiful letterpress studio with a Vandercook, type and floor to ceiling windows with a gorgeous view of the bay. That’s how I got started. Jack Stauffacher was teaching.

I got my first printing job at a quicky print place that was being run by a young guy. The owner had gotten popped for running smack. He would come in with his wife and two-year-old. I was running the front desk and there was a printer and a young guy who must have learned his chops in a JD program, anyway he was in charge because the boss was on trial for smuggling heroin. The three of us were there and the owner’s parole officer would come in saying, “What’s going on? Where is so and so?” I would say, “I know nothing. I’m not involved in this.” Then I got various jobs where I could run the presses and I was going to school, studying with Jack Stauffacher hand setting type. By 19 I was I am going to be a printer. I am going to be a printer. I’m going to figure this out. How does this work? It seemed like there were so many directions that one could go with it—literature, visual art, publishing, work for hire—there seemed no end to the possibilities. I wasn’t painting myself into a corner. And we were all anti-corporate at the time anyway, completely, so that wasn’t an option.

Kent: What were those early years like?

Felicia: This was in 1974 and it was 1977 when I started the press downtown in Santa Cruz. I had some really good support from one of the faculty at UCSC who was doing design work for a gallery. He designed a very nice, flexible, attractive announcement for the shows each month. That was my first job–resetting the line of type for the artist, getting the paper, mixing the ink color–I had some regular work. Then my reputation started to grow.

I had a partner when I first started, Maureen Carey. We remodeled this little tumbling down garage with sheetrock, to keep it from falling down, put presses in there and just started printing. Gradually the work came in. But it was never enough. Never enough to rely on or to grow. I thought it would grow. I hoped it would grow. But there was never enough letterpress work. I did job work for more than ten years. I started teaching workshops in the garage for the university. That same professor, Hardy Hansen, sent his best students to me to do independent studies. I also taught workshops for the public.

The press was a very public environment. It was a really sweet space and a good time. Eventually it was time to move on. I had a baby, a big life changer that changed my focus and I needed to stabilize my income. When my son was about six or seven I started working as an administrator part time for the university. This job really facilitated everything. The steady paycheck was fabulous. I could still do my commission work and teach, and still do Moving Parts Press. It really meant a lot that I was no longer scrounging from job to job, feast or famine.

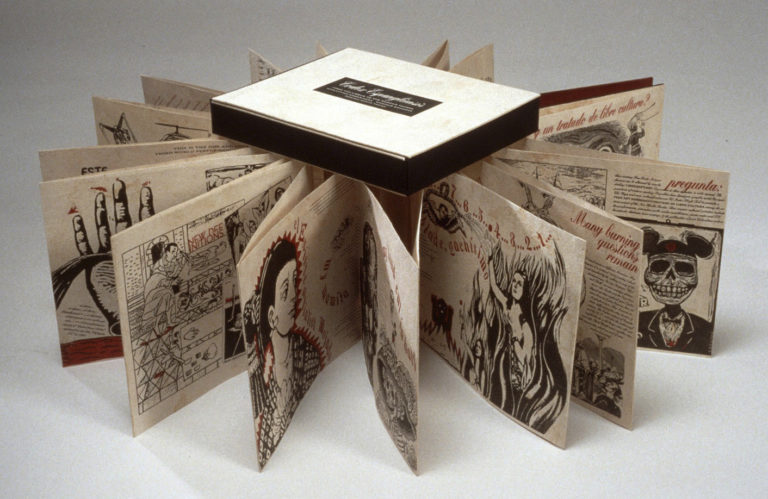

Felicia Rice with CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS from Columbus to the Border Patrol

Kent: You identify yourself as a publisher. What is the role of the publisher?

Felicia: The publisher makes the project public, selects the participants, finances the project. The beauty of being a publisher, coming from a family of artists, is that you are responsible for making it public. There is no waiting around for a gallery to pick you up and sell your work, and if they don’t, well you didn’t quite make it, or no one really likes it. There are none of those questions because it is your responsibility as the publisher to make it known, and if you don’t make it known the onus is on you, not on anyone else. It’s so freeing. It is also a huge responsibility, the financial part especially.

Kent: The new digital tools—desktop publishing in the mid 80’s, desktop video editing and interactive design in the 90’s—shaped not only how things were done, but reflected the changing landscape of information distribution. You employed these contemporary tools and sensibilities with methods of incunabula publishing from the late 1400’s. How aware were you of this unique position and how did the pros and cons of publishing in this manner influence your work?

Felicia: In the 90’s I was directing a graphic design program. From what I can tell design has been very catholic, there has been a full spectrum of approaches going on for a while now. A designer is known for their style. When I was coming up the ideal was the Swiss School: the grid, sans serif fonts, the rules of typography. We were teaching that in our design program as the foundation. When anyone asks me these days I say go to the Internet and look up the rules for typography. You’ll get ten, you’ll get five, and you will be fine. There is not a lot of misinformation about this stuff. You can go and learn those rules and apply them, but for me it was about going beyond the rules because I kept producing the same beautiful and elegant page over and over. I didn’t feel that for my own work that was enough, to keep doing the same thing again and again even though digging a deep hole was really important editorially for Moving Parts Press, first by publishing feminist writers, and then local, regional and statewide writers, and then national writers, until I finally landed with the Chicano writers and have stayed in this vein for 25 years.

Kent: Did you start with feminists writers?

Felicia: Yes, my first book in 1980 was a feminist poet. I could have continued with that, should have continued with that. As a publisher it is so important to establish an identity, to have a niche, people come to you and you go to them. . . and the audience expands. But I kept on moving along exploring different genres of poetry.

It wasn’t until the early 90’s that I started working with the Chicano writers and artists and discovered a home, a place where the community was so inclusive. By that time I had something to offer as a bookmaker. My first book in the series was with Francisco Alarcón. Everyone who knew Francisco recalls how inclusive he was, how he was always talking up the community and connecting people to each other.I also did another book with a colleague of his, Elba Rosaria Sánchez. I offered to do a chapbook for a poetry class she was teaching. I went to the final for this class and she had every poet get up and read. So that was telling in and of itself. There were eleven students and each one got up in the front of the room to read their poem and stayed up in the front of the room. It was about the gathering of their voices, not just any one poem. They were all there together and the applause at the end was for all of them. It had this wonderful group building community feeling. I felt included. That wasn’t always the case with some other poets and readings I had experienced where there was a lot of posturing, and a lot of difficulty, being a young woman. I got a real charge and felt a lot of goodwill. So that was the group that I started to focus on. I also began an alternative focus, the French Livre d’ artiste series. I did a couple of books in that genre, but then became so involved with the Literatura Latino/Chicana Series and got sucked into these major projects.

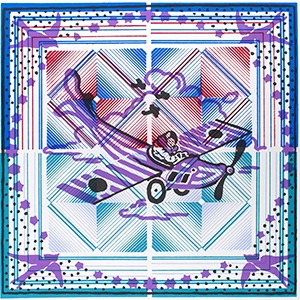

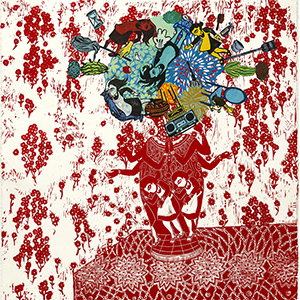

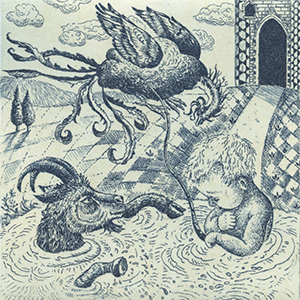

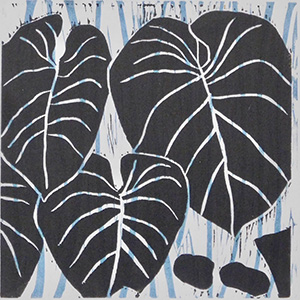

CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS from Columbus to the Border Patrol, Performance texts by Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Collage imagery by Enrique Chagoya, Bookwork by Felicia Rice, 1998

Kent: How do you conceptualize a project and select collaborators?

Felicia: In the 1990s when I was working with Francisco, the community builder, I asked him who he thought I should publish. I wanted to know who the leading voices were in his world. Those were the people I wanted to work with. By that time I had realized it was critical to publish someone who was a good performer, who went out and read or performed, and could sell books. If I had a wonderful poet who sat in their office and the books sat in stacks, that didn’t work from a publishing standpoint at all. Francisco said, “I know that Guillermo Gómez-Peña and Enrique Chagoya want to work together on making a book. You should go to this reception at the Mission Cultural Center on this night and they’ll both be there.”

So I put my books in my portfolio and I went to the Mission Cultural Center in San Francisco and I approached them. I had never met these people before. I didn’t know what they looked like. It was pre-Internet, it wasn’t like you could just look someone up and see their photograph. I had to figure out who they were. I started showing them my books and they were totally on board, immediately. So that was a shot in the dark as opposed to working with people that I had previously met and saw how they operated, and knew their personalities. I didn’t know these people and they didn’t know me.

Kent: My first exposure to your work was with that particularly stunning book, CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS from Columbus to the Border Patrol. Tell us about making this project.

Felicia: When the artist, Enrique Chagoya, gave me the images I think he may have thought I would put a word here and a word there. But the author, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, is about language. He’s about words.There is not one word, there is a full flood. Integrating the two together was very hard. My training in design and typography, was about the elegance of typefaces that demanded an elegant treatment. The CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS needed to go in another direction and I was struggling with myself the whole time.

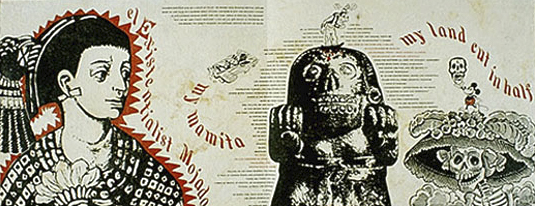

Pages from CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS from Columbus to the Border Patrol

It took two years for all of the images and the text to come in and then I took about three years to design and print and publish it. I was struggling with my own internal voices that were saying that I needed to make this very clear, that people should be able to read it, that it should have a certain type of fonts, that the print quality should be crisp and the ideal. And none of those things were happening. I was breaking my habits. It was very challenging but it was also a great education for me. It took me so long to make the book I am sure they lost faith completely that this nice white lady was making the book somewhere, like maybe. And I was working really really really really hard to make the book, to have the money to make the book, so finally when it was completed five years later they had to concede, that first there was a book and second that maybe the five years had been necessary, that the process required it.

Kent: Did they communicate content together or did they each just give you content?

Felicia: So what happened was they were really really old friends from the same stew. They knew each others’ work intimately and wanted to do something together. They had a sense of one another. Enrique was to provide the images and Gómez-Peña the text. Enrique was already making books and they knew his style; the difference was that his books didn’t have as much text plus CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS is 30 feet long, instead of nine. I do think that those two things make the CODEX very different than the kind of books Enrique makes himself. I do think that Enrique expected less text to accompany his visuals.

Kent: Did Gómez-Peña have the visuals first?

Felicia: No, the text just came to me. I got this and then I got that. Then I marinated the two. Made the decisions. I got 15 spreads from Enrique after about a year and a half. So it wasn’t like I was twiddling my thumbs for the first two years. When they came in there was no sense of sequence. Was there a sequence? What is the sequence? One of the beauties of this kind of linear collaboration is that when it is your turn you are left to do your thing without anyone meddling, or questioning or throwing in random ideas. I really was left to myself with these images, what to do, and then, BRRRINNGG! In comes pages and pages and pages of text from Gómez-Peña and I had no idea what they were. I went to see him perform but I don’t think I really 100% got what was going on with the text until I worked with Gómez-Peña a second time.

Kent: The sequel to CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS, Documentado/ Undocumented Ars Shamánica Performática, is a multi-platform project with many collaborators. Tell us about this project and how it came to be.

Felicia: Seven years later Gómez-Peña contacted me and said, “Gustavo Vazquez and I are making a video and wonder if you want to make a book in response.” Apparently a German curator told them, “You are making these videos but to exhibit the work what you really need is an installation of some kind. What about a book.” So Gómez-Peña says, “We are thinking about you, or this Spanish publisher/bookmaker might be interested.” I thought about it a bit and wondered, Is that going backwards to work again with Gómez-Peña’s scripts? I thought, No I could go forward with this and some things would change. He encouraged that I act as the visual artist and I jumped on that.

So with the first book I got all of the images and sheafs of text, which I thought of as poems and they are not poems. They are performance scripts. They came in 14 point type with totally uneven punctuation and use of italics. From an editorial perspective I was Wow! What do I make of this presentation here. Should I be squaring this all up and making it uniform. So I tried. It wasn’t until I went and took a performance art workshop with Gómez-Peña and worked with his scripts again in 2011 that I got it, that these are performance scripts. The type is large because they are used on stage. The line breaks are cues. You have to be able to glance at the script while performing and get it.

And then he wasn’t giving me new work. He was giving me work that other people had already published. I’m thinking, Really. What’s going to distinguish this? My literary publisher is going off in my head. He’s already published these, and they need lots of editing, and the grammar is strange. But I went ahead and worked with them and later on I got it. These are performance scripts, the re-printing and the re-issuing and the re-presenting himself on the stage, over and over, the shuffling, the adding new stuff–these were iterations. I had seen some of the scripts for DOC/UNDOC before, but to me they were a little different. They are living documents. Oh. I’m not codifying or capturing or fixing. I’m part of something that is living and moving forward. That made everything that happened with the CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS make so much more sense. And my treatment of it. I think I understood some of this when I worked with the text in the 90’s but when I worked with it again in 2011 I felt like I totally understood this now.

I don’t know about you but I have felt with this work that I am punching my way out of a paper bag. It can be so frustrating, so few guideposts, so little information, trying to create some order, trying to create some pathways.

I went to see a colleague in LA and we were talking about the business, what’s going on, what’s selling, and finally I said, “There is a path. I am on the path.” And she said, “Yes.” Sometimes you need someone to tell you that you are not making it up even though you are making it up, that there are other people on the path with you.

Pages from CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS from Columbus to the Border Patrol

Kent: You initiated the collaboration between Chagoya and Gómez-Peña and then you found yourself to be an integral part of the collaboration because you were not given direction. Do you think that was one of their objectives all along?

Felicia: Yes. They had given me the high sign. They had seen my work. Collaboration doesn’t have to be linear. It can be a mix where each person does their own thing, or someone else picks it up and you meet periodically, or interact via email or letters. When it’s your’s, it’s yours. When it’s your responsibility, you take responsibility. That’s the expectation of the group. Gómez-Peña is an amazing collaborator because he gives you so much agency. It is yours. Take it. Run. I was not confined to the structure or the look or the expectation that it would be like the book I made before. It could be something very different because whatever might dictate something else.

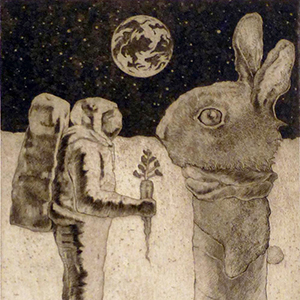

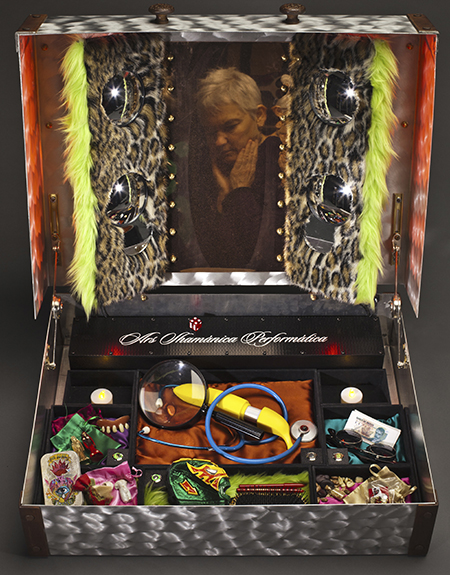

Kent: The Amate bark paper was a meaningful and elegant choice for CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS; and I see that you have used both boxes and cases for other projects such as El Alphabeto Animado. How did you come up with the concept and the ingredients for the shaman’s toolkit that goes with the deluxe edition of DOC/UNDOC?

Felicia: The cabinet of curiosities has its roots in the origins of the museum, private collections by wealthy individuals during the age of exploration. By the 19th c. even the middle class had collections in their parlors. Today we have photos and mementos in our own homes. The other sources for the cabinet of curiosities are the work of Marcel Duchamp and his Boite-en-valise created in the first half of the 20th century, and the work of the Fluxus movement in the 1960s. Both explored repurposing everyday objects, such as books, as art. Our concept is that immigrants need ritual and ritual objects to navigate the transformation required as one crosses borders. The objects in DOC/UNDOC are some of those that our collaborative group thought would help in this process.

Kent: What are the challenges of collaboration?

Felicia: I developed a list of five things that are required in collaborative relationships. These must be addressed up front.

The big one: 1) Mutual Respect. It’s huge. 2) Someone has to manage the project. 3) There has to be an understanding of the finances up front. There doesn’t have to be enough money, just an understanding up front. 4) The overall concept needs to be of shared interest, and 5) the project needs to generate opportunity.

Collaboration is uncomfortable. It’s not easy. It doesn’t just flow. On the other hand it can be uncomfortable, uneasy, and flow. It’s all going forward. All the parts are moving. It just is a matter of making it to the end.

Collaboration is an emotional rollercoaster on a certain level. I bring everything I have to it. I put everything on the line and my collaborators may not be doing that because it’s not their full time thing. It’s my full time thing.

Kent: Share some of the ups and downs of your 40 years history as a collaborative print and book artist and publisher.

Felicia: Ups: I knew early on that one book or project would not represent the effort or the identity. I started making books of poetry that people could afford, but there were other people doing that so well, presses doing knock out work. At some point I realized that there were books in me that only I could make, and that I needed to make books that only I could bring to the table. That has been the high point, actually starting to make things that not only challenge me but represent my vision. If I could only have only one book represent me it would be the most recent book, DOC/UNDOC.

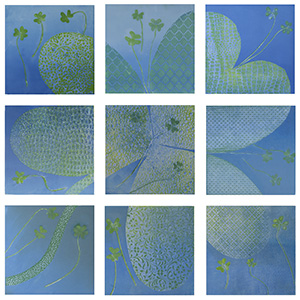

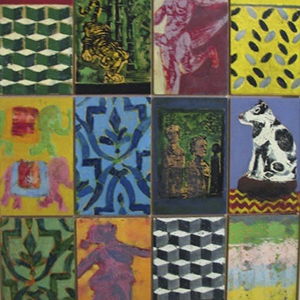

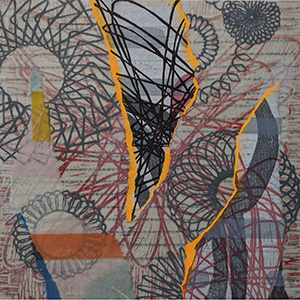

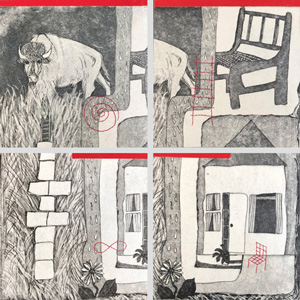

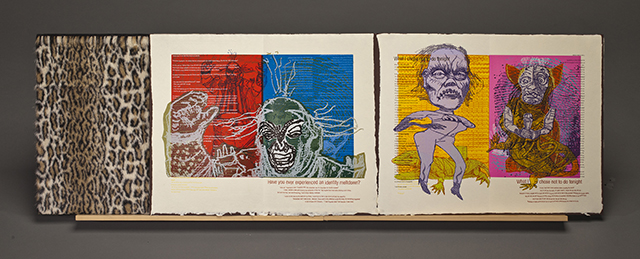

Documentado/ Undocumented Ars Shamánica Performática

Downs: Struggling financially for so many years. Obviously I would be in a better position if I had taken that corporate job. I interviewed at the type design studio at Adobe in the early 90s, and they didn’t accept me because they said people like me had been tried before and it turned out they couldn’t sit at the computer all day. We all ended up sitting at computers all day! But I did apply for the director job with the Art and Design Department at UCSC Extension. There were 80 applicants. I handcrafted my portfolio and everything that went into it, and I got the job. I was going to give up the press and go to work full time. They started introducing me around but it turned out that they couldn’t hire me because the job description required a higher degree. I only had a BA. So that was a glass ceiling. Four months later they asked me to manage the design program, a little piece of the department, and I did that. That started the administrative path. The teaching never took off as I hoped.

Kent: In the mid 90’s your design aesthetic advanced graphic design’s transition from more calculated Swiss Modernist sensibilities to screen-based layering of coded information requiring non-linear reading. At the same time, other West Coast design pioneers, including April Grieman, Rebeca Méndez and Lucille Tenazas were likewise pushing boundaries. During these years, what was your awareness of this major shift in rethinking visual communication?

Felicia: I was working in the design community, hiring faculty to teach design courses from all over the Bay Area, riding the wave. So I was looking at a lot of design. We would have people in to give lectures on the history of design and I would sit in and listen. I started out by teaching Quark. I didn’t even know what Quark was, all I knew was what Quark was supposed to do. By the time I was making CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS this type of stuff had been going on in the design community for years. I was aware of this type of experimentation and I didn’t think that I was that original. Anyone who knows David Carson’s work knows what is going on in my work. I understand it may have been ground breaking in the artist’s book world, but certainly not in the design world. I was always super interested in the tools and what they could do; certainly I haven’t exhausted that. When I added the whole digital realm to what is possible with relief printmaking it just exploded exponentially. For me, the importance is continuing to explore and learn. What’s possible? What can be done?

Kent: So you had the awareness of the shift in the design world, and you mention this in your work with Gómez-Peña. Talk about why that worked for his voice versus a more traditional Swiss Modernist approach.

Felicia: DOC/UNDOC performs the text in the absence of the performance artist. We call this a performative artist’s book for that reason, bringing it to life. The book activates the page, energizes. He activates the stage. Everything starts focusing in on him, all of the energy comes out of him.

How does a book do that? Instead of that very passive page that is inviting you to participate, the intent is that the page will reach out and grab you and pull you in. The moving type, not just rectilinear blocks than in CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS, was my way of invoking his voice. In DOC/UNDOC, the type is much simpler, but I did add a lilt to it to give it more of a conversational human voice, so that it is not simply marching letterforms on a baseline. They do travel a little bit. It is more of a waver. I wasn’t so concerned about readability in either book. I was surprised later when people said they could read it. I was ready for it to not be readable. Lines were left broken and words were left out and you can’t see all of it.In DOC/UNDOC I buried the text in the more active visual space. But the type is there. It is running down one side and upside down the other. You can read some, but not all. I also provide the text in a pamphlet that is included in the limited edition. All of the text is there to be read separately from the actual printed codex. Here in DOC/UNDOC and in the CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS it is meant to represent how we perceive the written word in this more and more visual culture, and that it is less and less important on the visual page. Take CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS, which is simply black and red on a creamy background, the type may waver and move around the page. Then go to DOC/UNDOC where the type becomes different colors and just another layer of thirty on the page, pulling the text out and deciding whether to read it or not is up to the audience, not something that I am requiring. I have a pull quote on each page that is the essence of what’s on that page, but it is not expected that you read the entire script.

Documentado/ Undocumented Ars Shamánica Performática

Kent: Talk about text in the age of sound bites and scanning and tactility in the age of smart phones.

Felicia: This is some of what I am talking about in terms of visual versus literary culture with emphasis on the visual, some of the text is integrated into the visual without a full commitment to maintain its legibility. It may just not have legibility any longer. This is the shift that we are seeing in popular culture.

It’s video that we are talking about with smart phones. My son was showing me how Instagram has a video component where you can integrate text right onto the movie. I saw it. It is everything I was thinking about for my next book. A person can be talking and you can drag text in around their chin. You can type right on the video and wrap the text around the moving image. The fact that someone took the time to make a component that allows you to wrap the text around the chin is a comment on how important text still is. That you can do this is a statement that text is still important. It’s still fun to text your friends, get text, add text or comment on your images. The language is still important. We have both the spoken and the written word. It’s still all going on. I don’t see text disappearing. I’m not saying its the end in our culture, but it certainly is shifting, and how it plays out is interesting.

Kent: Did you observe a shift in the way people read CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS and DOC/UNDOC?

Felicia: CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS is 20 years old. It has traveled all over the world. I received a communication most recently from a graduate student in India who is writing their dissertation on the CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS.People are scanning more, gleaning. The Internet has changed the way we read. It used to be about a finely designed page. That’s not how design works these days. People just grab what they need and then on to the next page. I think about that as I work with more complex images—take what you need and leave the rest, hopefully the meaning will still be there. That’s definitely how I approached the DOC/UNDOC project. My own sense of that started with my work on CODEX ESPANGLIENSIS by integrating the text onto the pre-structured pages.

Kent: Tell us about the transformation that led to your work as a performance artist.

Felicia: One way to think of the design process is that there are four components and it’s not linear. Every designer works through them in their own time and place and way. They personalize it.

So this is my take on Art versus Design. Design can be taught. There is a standard of excellence. This is a craft. The art process is very personal. Say you want to be an engineer or a doctor. You get on the train and then when you get off of the train you are an engineer or a doctor. An artist never gets on the train. An artist gets on their own train, makes their own path, goes on their own journey. This is why you don’t teach art, you model it. A student can go to an art school or read books to learn about the process by studying, but the main way to learn is by modeling and then you pick which parts work for you.

With design the steps are research, creative thinking, critical thinking and implementation. You could start with research, maybe. So with DOC/UNDOC, not early on, about four years into the project, I thought I really needed to go and take a workshop with Gómez-Peña and experience his performance art pedagogy to further understand what was going on with these scripts. So I went to his performance art workshop in San Francisco. There were 26 people from all over the world. The first thing you do in these workshops is introduce yourself: where you are from and what your intentions are. I could not say that I was there researching Guillermo Gómez-Peña so I said I was a book artist looking at being a performance artist. And that’s what happened. I explored Who am I? I found it to be so liberating and so freeing creatively. It made perfect sense that in making a performative artist’s book I made that transition myself. I took my work into a new realm which I am still very engaged in. What I would like to do is create a spoken word piece for each new book.

Kent: What did you learn about yourself from the process of becoming a performance artist?

Felicia: This is an open question. I am just beginning my work as a performance artist. One aspect has been incredibly freeing, the development of the scripts. They have a poetry to them but are not “poems.” In my mind poems are resolved works that are the result of intense internal debate over language and form, content. Scripts are much more fluid. Is the audience responsive, does the story hit home?

The scripts can be rewritten, updated, resequenced. Most of my life I’ve been challenged to write poetry myself, at the same time that I have been working with poetry as a printer and publisher. To be able to write without dealing with the personal and professional trappings of the business of poetry, the world of poetry, has been very liberating.

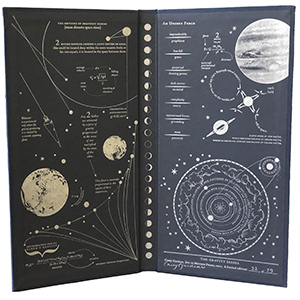

DOC/UNDOC, Felicia Rice with Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Jennifer Gónzalez, Gustavo Vazquez, Zachary J. Watkins, 2014

Kent: How has the physical and cultural environment of Santa Cruz influenced your creative work?

Felicia: I’m giving away this little piece (indicates the letterpress printed broadside/exhibition/keepsake announcement) which is actually a performance script in which I speak of the cadre of people here who make books or are writers. It is a very creative community.

What I always say about Santa Cruz is that she is very beautiful, but she is not generous. I have worked my ass off here to survive and continue doing my work. I don’t own any property here and have no hope to. It has no hold on me other than that it has been my home for so many years. It’s just enough. It drew me because of the university and the opportunity to change my mind if I didn’t want to be a printer. It’s proximity to San Francisco has been great. I’ve been living outside of town now for 25 years. It’s been fun having this show downtown because I lived downtown and had my shop downtown for 10 years. It’s like old times. The university also became a real home between being a student and working there. I am a coastal Californian originally from the little town of Mendocino. Santa Cruz was the next rung up from a little town to a town with a university and opportunities. That was as far as I got.