Instead of Invisible: Treading the Path of Elizabeth Catlett—

Black Woman Printmaker and Art Teacher

by Veronica Hicks

California State University, Sacramento

Veronica Hicks, PhD, is an art teacher, arts-based researcher, and author who explores themes of gender, race, and ability through narrative inquiry and collaborative art-making. As assistant professor of art education at California State University, Sacramento, she advocates for art students from diverse populations. Hicks lectures regionally, nationally and internationally in Africa, Europe, and Scandinavia.

Abstract

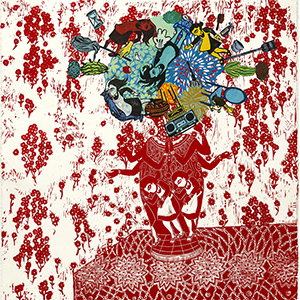

This essay employs my critical race and intersectional feminist lens to survey the connections between a historical and iconic Black woman printmaker and art teacher, Elizabeth Catlett (1915–2012) and my own lived experiences. This essay reflects the tumultuous times of Catlett’s and my early life and careers by disrupting traditional inquiry with visual aesthetics of art and poetic text. I use creative writing to understand the lives and work of Catlett and myself; two Black women printmakers and art teachers living in different times. I name sections after some of Catlett’s most famous prints and spread the poems throughout the essay to displace the reader’s attention. As Catlett’s contemporary, I juxtapose her and my art as a way of knowing, debating whether our similar identities bears weight on our experiences. Black Lives Matter activism pulses as the center of national unrest in this historical moment, not unlike Jim Crow laws and the Black power movement that Catlett experienced. I title the essay to quote Elizabeth Catlett in an archived interview (2010) with the African American Oral Histories at the Library of Congress American Folklife Center. She described reasons to work with Black women as her subject matter, stating “I was going to try to make people see [Black women] as beautiful, dignified, strong people instead of, as Ralph Ellison says, ‘invisible’.”

Introduction

As an art teacher in the United States, it has been challenging to identify an iconic mentor that reflects a similar identity to my own. Artists sharing my identity have historically been overshadowed by artists who are white men (Nochlin, 1971). Women of color printmakers and teachers remain, for the most part, invisible. To study a Black woman printmaker and teacher with a successful career, I studied the life of Alice Elizabeth Catlett Mora, hereby referred to as Elizabeth Catlett. Her journey to notoriety seemed exclusive to a Black woman of her talents and educational lineage. On the surface, I share commonalities with Catlett’s life. Upon investigation, I also shared her stance on democracy in education and art. Although living at different times and places, Elizabeth Catlett and my artistic and educational lived experiences align in a multitude of ways. I desired to discover whether our identities played a role in the ways our lives relate. In essence, were Catlett and I more connected instead of disconnected, visible instead of invisible?

Students Aspire

I read my father’s first, second, and third grade report cards.

Discolored with age,

progress reports were hand-written, composed in elegant, cursive ink.

He was failing. It was recommended

he should be held back.

I imagined the hand gripping

the fountain pen.

White, overworked, and dispassionate.

“My teacher hated me,”

my father exhaled,

“he made it nearly impossible to learn.”

I heard stories about my father’s teaching career as a community college instructor in northern New Jersey. Students stayed in touch with him for years after they had come and gone from his classroom. Where he came from, Trenton, New Jersey, children did not aspire to accomplish teaching at the college level for their careers. During the 1970s, the city valued skills over degrees. Survival was priority, not education. Like my father, my mother was the first person in her family to graduate college. An art teacher for over 25 years, her strong certainty that art education could change a student’s life for the better influenced my beliefs as an art educator. Both my mother and father were confident that education could bring good to a troubled world. With their encouragement, I stayed in school and began to express myself through paper, metal, and ink.

Elizabeth Catlett’s designation as an artist-educator could be attributed to her parents, who were both educators. Instead of invisible, Catlett’s parents were active members of their local academic community. Catlett’s father died before she was born, but was a professor at the Tuskegee Institute. Her mother was trained as a teacher and worked as a truant officer. Catlett observed the challenging educational climate for Black children in her home state of Washington, D.C.. Her early childhood experiences in urban populations set the stage for seeing familial success in educational careers. Catlett excelled when creating and studying art in school settings. At Howard University, Catlett earned her Bachelor of Science in Art, graduating cum laude, in 1935. She attended graduate school at the University of Iowa, then studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, learning lithography and linoleum cuts at the South Side Community Art Center. I recognized a pattern; Catlett was studying and working at premiere institutions while staying connected to people receiving education in urban communities.

Catlett and I share an awareness that scholarship is limited by the institutions afforded to us. A systemically racist institution, the urban education system failed students and their families for generations (Lewis, 2008). Systems of oppression count on children and their families to accept minimum effort instead of uniting to demand more opportunities or better resources. I question who benefits from a lack of educational reform for urban schools, which in many ways appear unchanged from Catlett’s time as a teacher.

What has drawn me to study art in school settings is what drew Catlett to art education. It is in my heritage, and part of my culture to survive and persevere. A piece of paper in my hand is proof that I can read and write—evidence of my knowledge in my craft and profession. Catlett was a similarly talented student who excelled in graduate school and was inspired to create art that reflected the subject matter she knew best. She reveled in a freedom of expression felt when handling ink and paper. This freedom must have been a welcome change from the constrictions of the oppressive societal structures of racism, sexism, and classism that was her reality.

I Have Always Worked Hard in America

Protest in our communities, in our physical and digital circles,

downtown invests in plywood instead of Black owned businesses.

Smiling in our faces

while behind a curtain

voting against our interests.

The failings of the United States’ education system have motivated me to invest my energy into educational reform. I seek change by working within the system by participating in state education organizations, volunteering to rewrite district curricula, and, ultimately deciding to strike as part of a teacher’s union. Catlett was also known to fight for the rights of Black teachers in her community. After spending two years teaching public school in North Carolina, Catlett united with then lawyer and later Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall in a failed effort to provide equal pay for Black educators. We still fight for equality today. In the aftermath of George Floyd’s death, Black Americans and allies rallied to bring attention to the dispensability of Black lives in the United States.

My Reward Has Been…Bars Between Me and the Rest of the Land

What is the correct response

when the only home

you’ve ever known

blatantly kills members of your race?

Instead of giving up, Catlett was persistent. She found a way for her Dillard University students to see a Pablo Picasso exhibition at Delgado Art Museum in New Orleans. The Delgado was off-limits to Blacks because it was located in a whites-only city park. Catlett organized a field trip to allow her class to visit the exhibition on a day the museum was closed to the public.

If designing a curriculum focused on Black artists in the United States, then the text, entitled African American Art by Samella Lewis would most likely be at the top of the reading list. Elizabeth Catlett was the first person to bring Samella Lewis to an art museum in 1940 as one of those Dillard University students visiting the Picasso exhibition. This small act that Catlett performed for Lewis echoes an unyielding commitment to the teaching profession; opening doors of opportunity and visibility for our students can become the act that ignites their greatness.

Catlett became an art instructor at George Washington Carver People’s School, a night school for the working people of Harlem. Her realization of ways in which her students’ lives were shaped by their economic circumstances deepened her awareness of educational and class privileges. Catlett recognized the working women at the Carver School having a cultural hunger to see themselves reflected in visual culture (O’Brien and Little, 1990). Inspired by her students, Catlett produced a series on the subject of “The Negro Woman.”

Representation matters. Seeking someone that shared my identity brought me to know Catlett, to see someone like me achieve professional success as artist and educator. Like me, Black and brown art students hunger to see their cultures reflected in studio art curricula, faculty, and their peer population (Kraehe, 2015). A lack of reflection could result in students of color leaving the field of art education and studio art. While a simple solution to the racial visibility problem in art education would be satisfying, what is needed are real, methodical changes steeped in accountability within educational institutions.

My Role Has Been Important…in the Struggle to Organize the Unorganized

I borrow brayers,

clip coupons.

I find a way.

To afford making art,

I borrow studio space,

share a printing press.

I will never stop

creating with ink and paint and paper.

Catlett left the United States for Mexico in order to complete her proposed “The Negro Woman” series. Catlett’s interests in Mexican printmaking spurred her to move to Mexico in 1946. She taught as a professor of sculpture at the national School of Fine Arts, San Carlos, in Mexico City in 1958. She earned a leadership role at the school as the head of the sculpture department. Catlett’s journey to department head reflects my own desire to provide guidance received by early career art students. Many of these talented individuals lack the institutional knowledge of how to successfully complete their degree. If Catlett worked with first-generation college students, her advice might assert that art supplies do not make the art—artists do. First-generation students lack professional, financial, and academic resources that create additional struggles in a competitive learning environment (Garriott and Nisle, 2018). These students can use low grade, low-cost materials to make impactful art when guided to apply their ingenuity and dedicate themselves to technique. In this way, art professors can instruct first-generation college art students creating without the aid of premium quality materials to become successful artists. Those on tight budgets purchase affordable art supplies, buying ink instead of paint, and paper instead of canvas.

Paper is a democratic medium. Catlett used paper to create prints to broadly distribute her ideas to the public. She shared her art by creating it at Mexico City’s Taller de Gráfica Popular. Translated into English, the Taller de Gráfica Popular means the People’s Print Workshop. The Taller was known to produce prints on cheap paper, then distributing the works in large quantities for their social and political messages to reach widest audiences (Cameron, 1999). Catlett shared the renowned printmaking collective’s commitment to accessible and affordable art, which resulted in her creating Black women-themed linocuts during her residency. Moving to make accessible art was the career move she needed from the United States, which, in 1946, was brimming with racial conflicts. From 1975 onward, Catlett lived and worked between Mexico and New York until the end of her life. Catlett’s legacy is a memorial to the power of making art that reflects social commentary. Instead of succumbing to societal pressures to accept mistreatment and prejudice, the art she produced raises the consciousness of Black women creating themselves. In the same vein, her life demonstrates the possibilities for social transformation through activism. Part of Catlett’s legacy that must be understood was her activism through education. Catlett started the funding for University of Iowa’s Elizabeth Catlett Mora Scholarship to provide support for Black and Latino students studying printmaking. She was confident, as I am, that art education can change the lives of Black and brown children.

This past summer, I squatted in a Berkeley studio space with a few tubes of ink and someone’s discarded poster paper. The tenant was vacationing in Europe for a month and gave me the building code. The studio space included a hand-me-down printing press, squeaky brayers of various sizes, and ancient printing barens. My workspace was not free; my payment to use the space was disposing of the communal trash and recycling bins, restocking the toilet paper dispenser, and refilling paper towel dispensers in the hallways. I wondered if the other artists who saw me performing these tasks had assumed the landlord hired a cleaning service. None of the studio tenants introduced themselves to me formally, although I did get curious looks paired with quick waves or smiles, hurriedly walking past me as I relocked the cleaning supply cabinet. The space was worth enduring the awkward interactions. The studio’s longest wall faced a playground. It was impossible to peer through the glass block windows due to their high placement, but I was able to enjoy listening to the familiar laughter and bustling activity of children just on the other side. I wondered if the children noticed which artists entered and exited the building. Did they observe that only white artists were able to afford rent? I don’t believe my presence at the studio was particularly notable to the children or the artists. My hope is that Black women artists occupying white-dominated studios becomes a common, unremarkable event. Until we are seen with regularity in these spaces, I will continue squatting, disrupting, and manifest divergence wherever possible.

I am the Black Woman

I reclaim marginalized visions of Black womanhood.

The space that we are in

ultimately changes lives.

What is the legacy of the Black woman artist and teacher?

Can teaching art as a Black woman be a radical act?

Catlett’s story is written, but mine is still being told.

We lived at different times and places.

But our artistic and educational lived experience is more

connected

instead of disconnected,

visible

instead of invisible.

My identity holds no preemptive barrier, rather, the cultural behaviors towards Black women artists and teachers complicates my understanding of what it means to be me, whether someone is Black/woman/artist/teacher or not. Instead of stagnant, Catlett recognized her view of her identity as constantly reforming, her experiences widening, worthy of documentation. I examined Catlett’s art and career choices, looking for reasons that she created works on paper and evidence of her commitment to providing art educational experiences for students. Catlett’s life and mine relate through our shared identity and upbringing, connecting again in other ways, such as our beliefs of equitable access to art and educational opportunities. We have witnessed injustices in art education and use our actions to change systems of oppression working against our students and towards our favor.

There is a need for those who believe in an arts education to become familiar with revolution. Any change made towards progress is a more feasible option than accepting more of the same oppression and subjection to invisibility. Notable figures who share in my identity and experiences, like Catlett, were there the whole time. The search for our own selves in the institutions we frequented made me consider my own successors, who, one day, might create and teach without worrying if they are seen.

Works Cited

Cameron, Alison. “Buenos Vecinos: African-American Printmaking and the Taller De Gráfica Popular.” Print Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 4, 1999, pp. 353–367. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41824990. Accessed 21 Nov. 2020.

“Elizabeth Catlett: My Advice to Young African Americans.” YouTube, uploaded by The National Visionary Leadership Project, 26 April 2010, https://youtu.be/EAl9xr5dbx8.

Garriott, Patton O., and Stephanie Nisle. “Stress, Coping, and Perceived Academic Goal Progress in First-Generation College Students: The Role of Institutional Supports.” Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, vol. 11, no. 4, Dec. 2018, pp. 436–450. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1037/dhe0000068.

Kraehe, Amelia M. “Sounds of Silence: Race and Emergent Counter-Narratives of Art Teacher Identity.” Studies in Art Education, vol. 56, no. 3, Spring 2015, pp. 199–213. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/00393541.2015.11518963.

Lewis, Chance W., et al. “Framing African American students’ success and failure in urban settings: A typology for change.” Urban education 43.2 (2008): 127-153.

Nochlin, Linda. “Why have there been no great women artists?.” The feminism and visual culture reader (1971): 229-233.

O’Brien, Mark, and Craig Little, eds. Reimaging America: The arts of social change. New Society Pub, 1990.

List of Figures

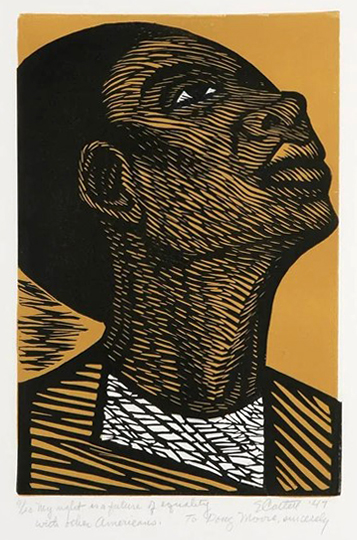

(from top, left to right)

Clarke, Bruce. Veronica Hicks. 2019.

Kelley, Jesi. Elizabeth Catlett Has a Show. 2009. Flickr Creative Commons, https://www.flickr.com/photos/thebearmaiden/3447190566/in/album-72157616764520361/.

Catlett, Elizabeth. My Right is a Future of Equality with Other Americans. 1947 (printed 1989). Catlett Mora Family Trust, Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society, New York, NY.

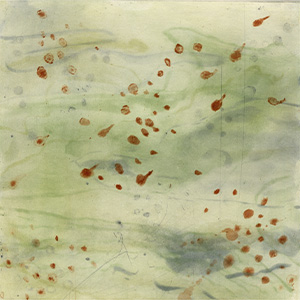

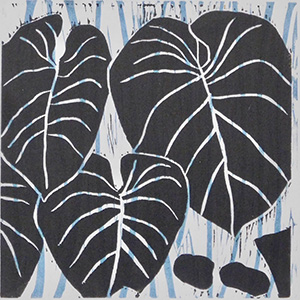

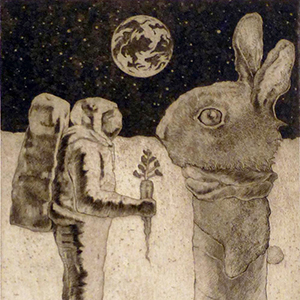

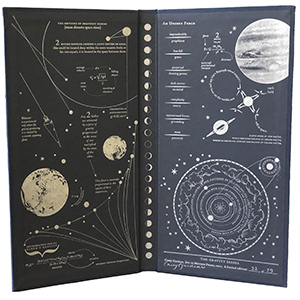

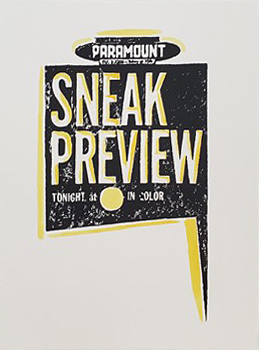

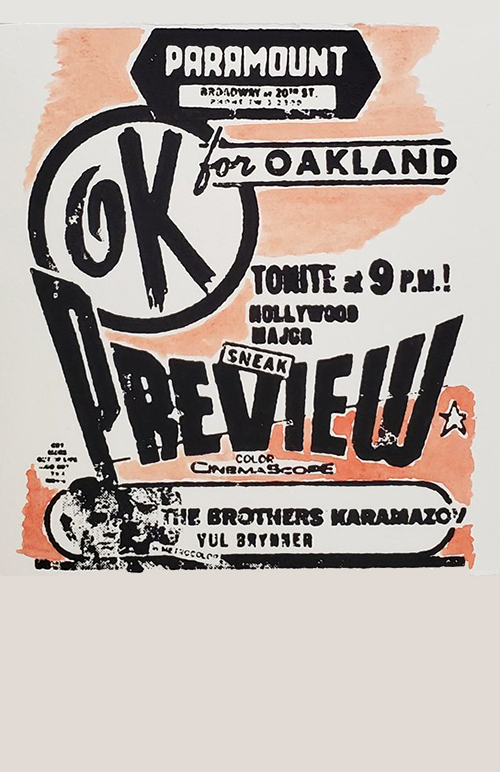

Hicks, Veronica. Sneak. 2019.

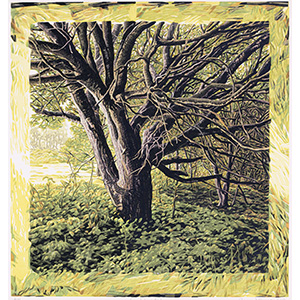

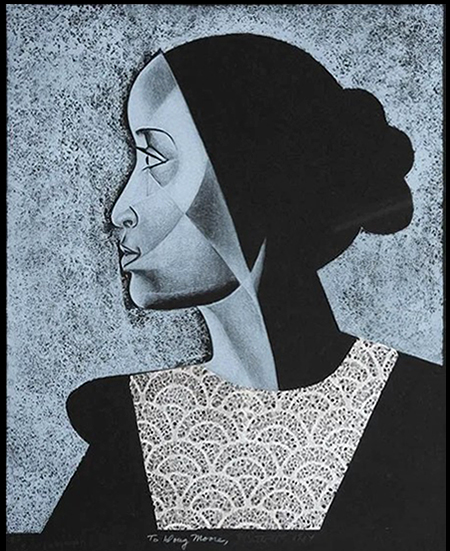

Catlett, Elizabeth. Virginia. 1984. The Cochran Collection, Copyright Wes and Missy Cochran, All Rights Reserved, https://bobartlettcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/BBC-CochranExhibition-Web.pdf. Accessed 14 October 2020.

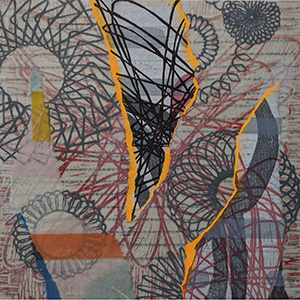

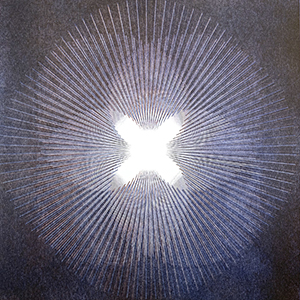

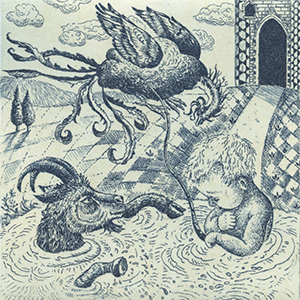

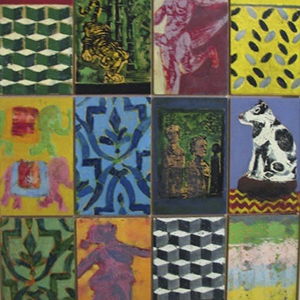

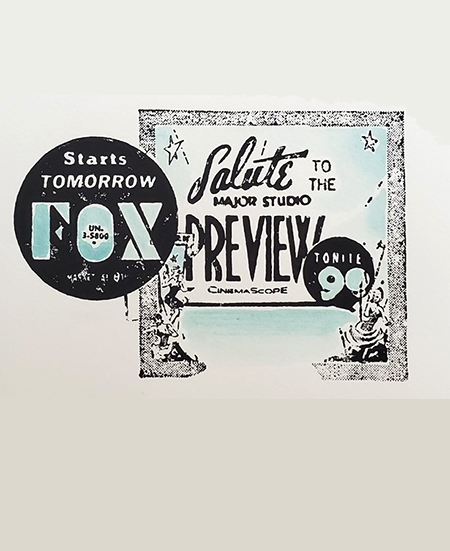

Hicks, Veronica. Siren Salute. 2019.

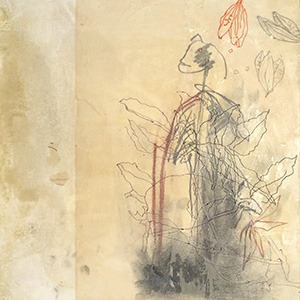

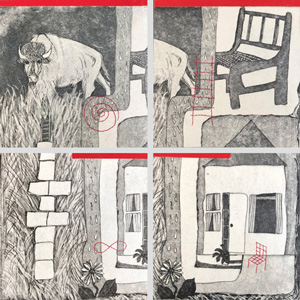

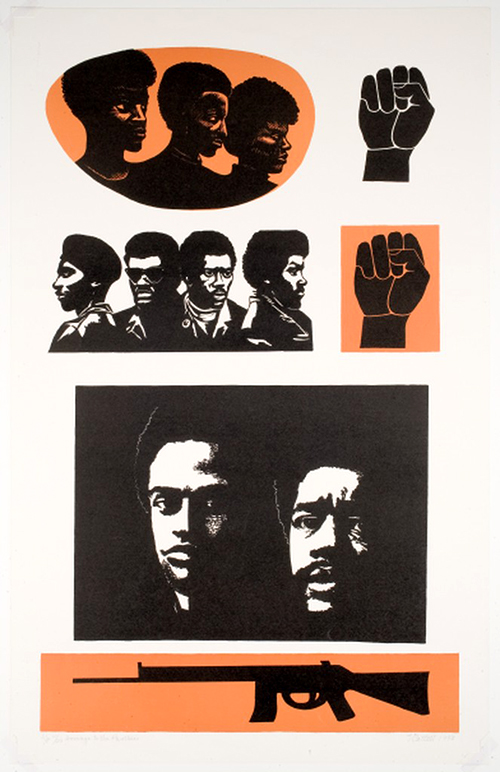

Catlett, Elizabeth. Homage to the Panthers. 1970 (printed 1993). Artstor, library-artstor org.proxy.lib.csus.edu/asset/AWSS35953_35953_42265631

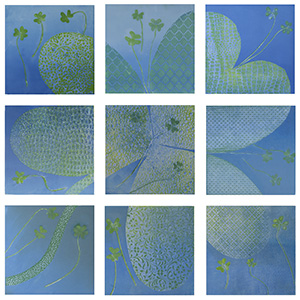

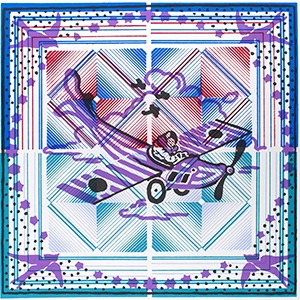

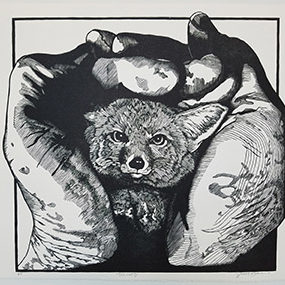

Hicks, Veronica. OK for Oakland. 2019.